Original Article: Surrogacy needs to be regtulated, not prohibited https://www.bmj.com/content/386/bmj-2024-079542

Our Response to Surrogacy needs to be regulated, not prohibited

Dear Editor,

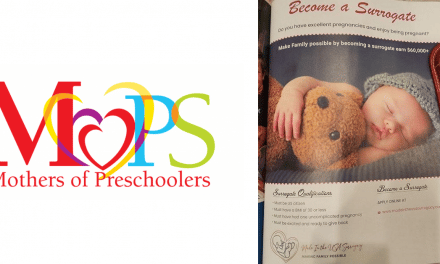

As nurses, we find it troubling that Lavanya et al. argue, as lawyers, for the regulation of the surrogacy market as a way to protect women and children. While we agree that Lavanya and colleagues have much experience with writing and executing contracts, they are not medical professionals. We have first-hand experience of the high-risk nature that gestational surrogacy confers onto women who serve as surrogates and the children they carry.

What are these risks? The short-term risks include high blood pressure, pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, premature birth, low birth weight infants, and from our own published research, “A Comparison of American Women’s Experiences with Both Gestational Surrogate Pregnancies and Spontaneous Pregnancies” we found these risks along with increased rates of postpartum depression after a surrogate pregnancy, when compared with pregnancies of the surrogate’s own genetic children. Further, our research found that surrogate mothers, especially Woman of Color, had increased complaints of chronic illness like abdominal pain, headaches, dizziness, and bloating further. Other research is showing children born through assisted reproduction are at risk for heart defects, musculoskeletal and central nervous system malformations, and as mentioned above, complications related to prematurity and low birth weight. It is well established and well understood in the medical profession that pregnancy is a full body experience, affecting the physical, social, mental, and emotional health of a woman.

Even if one study, referenced by Lavanya and colleagues, claims surrogate mothers have found it “rewarding and pleasurable”, we ask, how can regulation protect against medical risks and complications, like postpartum depression? We live and work in California, a reproductive tourism destination, where we have witnessed surrogate deaths, the harms, like loss of fertility and stroke, of egg “donors” who are used for some surrogacy arrangements, as well as fetal death as a result of these high-risk pregnancies.

Medical practice is beginning to recognize the importance of the fourth trimester, those 12 weeks post-delivery, where important physical and emotional changes are happening between mother and child. Bonding, attachment, breastfeeding, and healing, all normally seen as important and good, but often ignored and wiped away as unimportant in the context of the gestational surrogate pregnancy. In the U.S., we are troubled by the counterintuitiveness of practices where hospitals receive financial incentives to become more “baby friendly” in order to improve mother-child breastfeeding success, while commercial surrogacy practices prevents such success, failing to ensure infants, and mothers, the life-long benefits of exclusively breastfeeding whenever possible.

The practice of medicine is aimed at the health of their patient. The surrogate is not a patient and she has no medical need to put herself at risk to her health. We are deeply concerned that the surrogate is most often paid to assume these risks to her own health. The surrogate mothers who have died in the U.S. were young mothers. Their partners lost their spouses. Children lost their mothers. The authors argue that as it relates to health and safety, “laws which seek to restrict or prohibit surrogacy tend to produce the opposite outcome” is flawed. We maintain that laws which permit surrogacy do very little to protect the short and long-term health of women who are commissioned as surrogate mothers, as well as the children they carry.

Kallie Fell, MSN, BSN, RN

Executive Director, Center for Bioethics and Culture

Jennifer Lahl, MA, BSN, RN

Founder, Center for Bioethics and Culture

Author Profile

Latest entries

FeaturedMarch 5, 2025The Importance of Nurturing the Values We Hold Dear

FeaturedMarch 5, 2025The Importance of Nurturing the Values We Hold Dear FeaturedMarch 5, 2025Reproductive Exploitation: The Ordeal of Gestating for Others

FeaturedMarch 5, 2025Reproductive Exploitation: The Ordeal of Gestating for Others FeaturedMarch 5, 2025CBC Testimony on H.B. No. 7022: An Act Promoting Equity In Medicaid Coverage for Fertility Health Care

FeaturedMarch 5, 2025CBC Testimony on H.B. No. 7022: An Act Promoting Equity In Medicaid Coverage for Fertility Health Care FeaturedFebruary 20, 2025Press Release: Center for Bioethics and Culture Responds to President Trump’s Executive Order on IVF

FeaturedFebruary 20, 2025Press Release: Center for Bioethics and Culture Responds to President Trump’s Executive Order on IVF